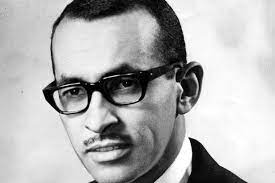

Black History Month spotlight: Wyatt Tee Walker

Wyatt Tee Walker was influential in the successes of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

This article is the third in a five part article series that will feature famous historical black figures for the month of February. This week’s feature will deal with Wyatt Tee Walker, a Chief of Staff for Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as a major influence in the success of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Walker was also a resident of Chesterfield County for 12 years.

Wyatt Tee Walker was born on Aug. 16, 1928 in Brockton, Mass. He humbly stated that his only claim to fame was his role as the Chief of Staff to Martin Luther King Jr. He was a freedom rider, a pastor, a child of the great depression and, as Chief of Staff, is widely credited for the success of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

As a young boy living in New Jersey, Walker lost a childhood friend due to racism. In an interview with David Cline, Walker opened up about his past.

“There was a little girl who lived about two blocks from my home named Nancy, and we used to play together,” Walker said in the interview with Cline. “One day she came to the curb from her house, and she was sort of crying, and she said she couldn’t play with me anymore. I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Because you’re colored.’ I didn’t even know what that meant, but later I understood it.”

Walker’s residence in New Jersey did not provide relief from segregation.

“The section of North, South Jersey that we lived in, … we called it Little Georgia, because it was so bad,” Walker said.

Segregation affected Walker’s education and shopping habits.

“My first schooling was in the segregated schools, and my first experience of integration in education was in junior high school and high school,” Walker said. “And in the town that I lived in, there was a drug store, and you couldn’t be served in it.”

The area Walker grew up in also had an active Ku Klux Klan presence.

“They burned a cross on one of Father Divine’s headquarters,” Walker said. “It was like growing up in the South, really, but I couldn’t compare it until later on in life.”

In the face of the prejudice surrounding Walker’s early life, he turned to his father as an example.

“He was always involved in trying to find some reconciliation between the white and the black community,” Walker said. “I grew up with a portrait of Frederick Douglass on the wall, and so I was very familiar with the history of our people in America.”

Walker would later describe preaching as, “…the best means of fighting segregation in any form that I found it.”

Walker later moved to Virginia and got a Master of Divinity degree from Virginia Union University. In his last year there, he was called to Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg where he preached for eight years. In that time, Walker found that Petersburg was in need of the reconciliation his father fought for in New Jersey.

“Everything was segregated in Petersburg when I arrived, including the ministerial alliance,” Walker said. “The first experience I had in integrating was integrating it with the chaplain of Virginia State and another pastor in the town,” Walker said in his interview with Cline.

Regardless, he was unable to integrate the library.

“For some reason, the NAACP would not make a case of it, and I felt they had pulled the rug from under me,” Walker said.

So, Walker emulated King and took action.

“I had a demonstration, and we went there on Feb. 27, 1960,” Walker said. “We went through the white door, [for] which we were promptly arrested in a few minutes … Of course, that was, back in that day, that was big news and unusual, because the black community of Petersburg had been so cowered by the system of segregation that they wouldn’t even think of trying to integrate a facility.”

In 1960, King offered Walker a position in the SCLC as a staff member.

“He invited me to become an executive director of the organization, to help build it into what became, in my view, the most powerful civil rights organization in the [19]60s,” he later told Cline.

Walker’s work would multiply the size of the SCLC staff twentyfold and increase their initial budget of $57,000 to $1,000,000. Walker described the SCLC as “an idea in Dr. King’s briefcase.” Walker’s efforts as an administrator and fundraiser turned King’s idea into one of the largest engines for the Civil Rights Movement and proponents of nonviolent protest.

Walker lived in Chesterfield County in his later years following his retirement. He lived in the county from 2004 until his death in 2018. In October, the county named the Enon Library building after him.

Jackson Bechtold’s interests lie primarily in graphic design and English. He’s a senior currently involved with the library, the film club, and this...

Seneca Wyche • Feb 16, 2023 at 9:47 am

awesome